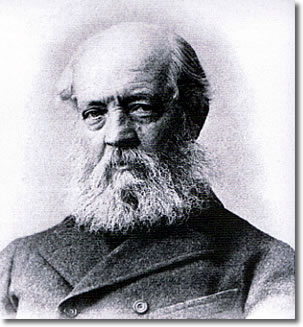

Frederick Law Olmsted's artistic legacy includes some of the world's finest public green spaces: Boston's Emerald Necklace, Hartford's Bushnell Park, Montreal's Mount Royal Park, New York City's Central Park, Philadelphia's Fairmount Park, Niagara Falls and California's Yosemite Valley are only a few of his thousands of works.

Born in Hartford CT, Frederick Law Olmsted (1822—1903) was the son of a successful dry goods merchant. Schooled by various New England preachers and at Yale, he was an unsuccessful farmer and successful travel writer before turning his attention to parks.

Traveling through the southern United States before the Civil War, he wrote newspaper and magazine articles critical of the slave economy, describing how it was not only immoral and degrading for all concerned, but also economically inefficient: free men worked harder and better than slaves who had no incentive to work and no freedom to improve their skills.

His experiences with farming in Guilford CT and Long Island and Staten Island NY were not great commercial successes, but he learned a lot about plants and soils, and made important personal connections in fast-growing New York City. With English architect Calvert Vaux, he drew up plans for New York's Central Park, then built the organization that would carry out this monumental work—with as many as 3600 workers at one point.

His genius for organizing large-scale projects won him an appointment as head of the United States Sanitary Commission, established to provide public health and medical facilities for the Union armies fighting in the Civil War (1861-1865).

Olmsted went on to head the huge Mariposa gold-mining operation in California, where he championed preservation efforts for the Yosemite Valley and the giant redwood forests.

Returning to the east coast, he again took up landscape design, which he developed into the new art and profession of landscape architecture, which progressed well beyond the park designs of old Europe.

Classical palace park designs of Europe extended structural architecture from buildings into their surroundings, creating formal gardens with geometric designs where there had once been wild country. Great buildings thus became bigger than themselves.

Olmsted perfected an art far better suited to the wilder American landscape: he crafted parks and open spaces that emphasized the inherent natural features and beauties of a place, enhanced them and adapted them to human aesthetics, increasing their impact. His goal was to create natural spaces that would give people not just pleasure, but important benefits: healthful exercise, relief from stress, and spiritual freedom.

By designing spaces in which all classes of society would meet and take pleasure, he sought to extend and empower an egalitarian, democratic ideal.

His parks were both works of art and important facilitators of social harmony. Many times his noble goals were frustrated by public officials and private powers-that-be who lacked creative vision, but he persevered.

The young United States, with its new, burgeoning cities, was incredibly fortunate to have developed a genius who graced these new urban centers with artistic jewels and foresightful plans that still, over a century after the artist's death, continue to enhance their daily life and society.

You can visit Olmsted's last home, Fairstead, in Brookline MA (next to Boston: map), now the Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site. He is buried in Old North Cemetery, part of the system of green spaces he developed for the city of Hartford CT (map).

For more on Olmsted and his works, visit the National Association for Olmsted Parks website.