Street Crime

The bigger the city, the more caution you must exercise. Avoid walking or driving through the poorest areas of a city, especially at night, and avoid walking in lonely, dark streets and parks.

If you must be out on city streets between 11 pm and 6 am, ask at your hotel about areas to avoid, and whether you should take a taxi rather than walk.

Pickpockets

Be careful of your wallet or purse in the subway, at open-air festivals and markets, where pickpockets sometimes work the crowds.

The modus operandi is for a group of four or five such types to ride the trains or buses together so the stolen wallet or purse can be passed from one to the other, thus protecting the one who actually lifted it.

Be wary of people who continually bump people and crowd toward the doors at a stop, and then "decide this must not be the place," and move back in. They'll be carrying coats or raincoats (whatever the weather) to conceal a light-fingered hand and also any prizes they may take.

If you see one in action and challenge him or her, the reaction will be aggressive defense—"Who are you calling a pickpocket?"—and then a quick exit.

If you should be so unlucky as to have your pocket or purse picked, contact the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority, Lost and Found (the phone number may depend on the subway line or bus you were on).

Try a few days later as well, since wallets are often found, minus cash, and turned in.

Tickborne Illness

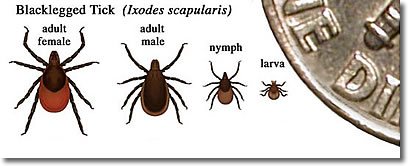

Tiny insects called ticks are Arachnidae, related to spiders.

Blacklegged Ticks (Ixodes scapularis, also called Deer Ticks), American Dog Ticks (Dermacentor variabilis), and Lone Star ticks (Amblyomma americanum) are common in the southern New England states (Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts) and are becoming common in the northern New England states of Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine.

You must be aware of these insects and prevent against the serious diseases they may carry. Don't let it scare you—just take the proper precautions and these diseases are preventable.

Blacklegged (Deer) Ticks

About 25% to 33% of Blacklegged ("Deer") Ticks in New England may bear and transmit serious illnesses including Lyme disease, Babesiosis, and Anaplasmosis.

The best defense is to understand the the ticks and the risks, and avoid them:

Adult ticks are about the size of a sesame seed,

larvae the size of a poppy seed: really tiny!

Larval Stage Ticks

Larval Stage Ticks are teeny-tiny! Tiny as they are, they may get on you, and they need a meal of blood to progress to the next stage in their life cycle.

Nymph Stage Ticks

Nymph Stage Ticks, the small insects after the larval stage, are also tiny: barely 1 millimeter (4/100ths of an inch) in diameter, about the size of a poppy seed, pen point or the head of a pin. Nymphs are the most dangerous stage of the ticks' life. They carry the highest risk and are responsible for most instances of tick-borne disease.

They attach themselves to warm-blooded animals, feed on blood, and may pass disease-causing bacteria when they do. They are active in New England from early May through early August, with May, June and July being the highest-risk months. Their bite is virtually painless, so you probably won't notice it.

Adult Stage Ticks

Adult ticks are substantially larger than nymphs, 2 to 3 millimeters (8/100ths to 12/100ths of an inch) but still smaller than the much larger Dog Tick.

Adults are active from September through the winter to May, except perhaps during hard-freeze conditions. September, December, January and February are the lowest-risk times of year.

33% to 50% of Adult Stage ticks bear diseases.

Here's more information on the life cycle of ticks.

American Dog Ticks

American Dog Ticks, which are larger than Blacklegged Ticks and thus easier to spot and remove, do not carry and transmit the same diseases as do Blacklegged Ticks. Dog Ticks may carry and transmit Tularemia and Rock Mountain Spotted Fever.

Lone Star Ticks

Also known as the Turkey Tick or Northeastern Water Tick, the female of this species bears a white spot (its 'lone star') on its back. They can carry a variety of Erlichia diseases, among others. Wild turkeys are a common host for this insect, earning it the nickname Turkey Tick.

Where You May Encounter Ticks

Ticks normally live in New England's forests, fields and lawns. Anywhere there are trees, plants, grasses or leaf litter, there may be ticks. They cannot jump or fly, but they can climb onto your shoes, then crawl up your socks and pant legs looking for a place to suck your blood.

In their habitat, Nymph Stage Ticks stay close to the ground. Adult ticks may climb plants, flowers and bushes up to a height of several feet (about a meter), from which they can climb onto you if you brush against the plant.

Ticks may climb onto and pass diseases to any mammal, bird, reptile or amphibian: deer, squirrel, mouse, vole, chipmunk, etc., so anywhere there are warm-blooded animals, there may also be ticks, including in the yards and gardens of houses, even in cities and towns, although the risk of contact increases greatly in forests and fields.

When Ticks are Active

You may encounter ticks whenever the temperature is above freezing (32°F/0°C)—yes, even in winter. The cold months of December, January and February, and the month of Sptember, have the least tick activity. The warm months of May, June and July have the most. April and August have much activity; March, October and November the next-to-least—but there are always ticks when it's not freezing.

How to Prevent Tick-Borne Diseases

So ticks may be almost anywhere outdoors. Don't let this curtail your enjoyment of New England's woods, meadows and fields. Just take the proper preventative measures:

Use Tick Repellent

Two types of insect repellent are effective against ticks. It's very importantto follow the instructions exactly when you use these strong chemicals. If misused, the repellents may not work, or may cause illness themselves:

DEET

Many insect repellents contain DEET (N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide), a chemical that makes it difficult for ticks to smell humans, and thus to be attracted to us. You can buy repellents containing DEET as liquid, lotion, spray, towelette, and other applications meant to be applied directly to the skin in areas most likely to be near ticks (such as feet, ankles, legs, hands, arms, etc. More...

Your Clothing

Consider wearing light-colored clothing so you can spot ticks more easily. Tuck your pants cuffs into the tops of your socks so the ticks cannot crawl right up your socks to your bare legs.

Permethrin

Permethrin is a powerful chemical that kills ticks on contact, but it is used only on clothing, NOT on bare skin!

Permethrin is meant to be applied to clothing well in advance of wearing (several hours), left to dry, then the clothing worn when pursuing activities in tick-habitat areas. So you must plan ahead to benefit from Permethrin's powerful tick-repellent properties.

You can buy outdoor clothing pre-treated with Permethrin that will retain its tick-repellent qualities through 70 washings; or you can buy sprays that have Permethrin as the active ingredient, spray your shoes, socks, pants, etc. under controlled conditions (read the label!), let the spray dry for several hours, then wear the clothing. If you spray it, your clothes may retain their repellent properties through about 4 to 6 washings.

Shower & Tick Check

Take a hot shower after outdoor activities in tick habitats, scrub all of your skin with a cloth, loofah, etc., and feel for ticks as you wash. Dry all of your skin vigorously with a towel. Then do a thorough tick check: front, back, feet, hands, limbs, butt, privates.

How to Remove Ticks

A good scrubby shower and vigorous toweling may remove ticks, but if you find one during your post-shower tick check, here's what to do:

Using pointy tweezers, grasp the tick at the head and pull it straight out of the skin. Do not twist it—pull it straight out, then apply antiseptic to the site of the bite.

Preserve the tick and note the date it was found and removed in case you want to have it tested for disease.

Chances of Contracting Disease

Finding a tick on you—even one that has attached and is feeding—does not mean you will contact a disease. The tick may not bear disease-causing bacteria (50% to 75% do not), and it must feed for a certain amount of time in order to communicate a disease. If you remove it by showering or during a tick check on the same day it got onto you, you may have no reason to worry. Still, monitor the site of the bite daily for a week or two, and contact your doctor.

Tick-Borne Disease Resources

US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Massachusetts Department of Public Health

University of Rhode Island Tick Encounter Resource Center

University of Massachusetts Tick-Borne Disease Diagnostics