New England History

Paradoxically, tradition and innovation have coexisted peacefully from the very beginning of New England when the Pilgrims arrived in Massachusetts Bay aboard the Mayflower.

Mayflower II, a replica of the Pilgrims' vessel, moored in Plymouth MA.

New England was founded by the Pilgrims, men and women who escaped the strictures of Reformation Europe to experiment with new religious and societal ideas.

They built a new way of life on this continent, but they included in it the things they loved best about the old countries they left behind.

But let's start at the beginning, long before any people were here at all: in Pre-historic times.

(If you want to go back even farther, see Natural New England).

Timeline

9000 BC Immigrants from Asia reach what is now New England.

1000 BC Norse mariners explore parts of the New England coast.

1497 Giovanni Caboto (John Cabot) lands on the New England mainland and claims it for the king of England.

1524 Giovanni da Verrazano sails along the New England coast, naming Rhode Island.

1602 Bartholomew Gosnold and colonists arrive in New England, name Cape Cod and Martha's Vineyard, and set up a colony that lasts only 22 days.

1614 Captain John Smith returns to England with a rich cargo of fish and furs from what he calls "New England," the first use of the region's name.

1620 Pilgrims aboard the Mayflower reach the tip of Cape Cod in November, and Plymouth in December.

1635 English settlers bargain with Native Americans for six square miles of land on which to found the first New England town beyond tidewater: Concord, Massachusetts.

1636 Harvard College is founded to educate young men for the ministry.

1638-39 Portsmouth, Rhode Island is founded; Hartford, Windsor and Wethersfield, Connecticut join to form the Connecticut Colony.

1692 Witch trials are held in Salem, Massachusetts.

1765-67 Passage by Parliament in London of the Stamp Act and Townshend Acts infuriate American colonists.

1770 Boston Massacre in March heralds the break between mother country and colony.

1773 Boston Tea Party on December 16th goads Parliament to pass strict laws strangling New England's economy.

1775 Minutemen of Lexington and Concord battle British regulars on April 19th, beginning the American Revolution.

1776 Revolutionary forces inflict heavy casualties on the British at the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17.

1777 Vermont declares independence from Great Britain as a republic.

1783 By the Treaty of Versailles, Great Britain recognizes the independence of the United States.

1790's Salem MA shipowner and merchant Elias Hasket Derby becomes America's first millionaire.

1790's Eli Whitney's cotton gin provides cheap thread for New England's burgeoning textile industry.

1820 Maine, once part of colonial Massachusetts, becomes the 23rd state.

1845 Henry David Thoreau builds his little house at Walden Pond in Concord MA.

1850s Boston, and especially Concord, Massachusetts, enjoy cultural—and especially literary—prominence by the work of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Bronson and Louisa May Alcott, Julia Ward Howe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Margaret Fuller, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Mary Moody Emerson, and numerous other poets, writers, lecturers and philosophers.

1852 Harriet Beecher Stowe's book Uncle Tom's Cabin becomes a best-seller, inspiring Abolitionists who seek an end to slavery.

1857 Discovery of petroleum in Pennsylvania sounds the death knell for New England's whalers and rich whale-oil trade.

1929 Stock market crash signals the end of New England's commercial and industrial greatness.

1944 World monetary conference held at the Mount Washington Hotel, Bretton Woods, New Hampshire.

1954 USS Nautilus, the world's first nuclear-powered submarine, is launched at Groton, Connecticut.

1960-63 John F. Kennedy, of Brookline, Massachusetts, serves as President of the United States.

1970's Computer boom brings renewed prosperity to New England.

2000s Technology, life sciences, research and medicine drive Boston's booming economy.

Prehistoric New England

Every New Englander, whether of aboriginal, European, Asian or African heritage, is an immigrant.

The western hemisphere was first populated by a Mongolian people who came from Asia, perhaps across the Bering Strait, anywhere from 12,000 to 25,000 years ago. They reached New England about 10,000 or 9000 BC.

We know very little about these first inhabitants, not even if they were the ancestors of the Native peoples who were here when the first European explorers arrived.

Stone-Age New Englanders

New England may be a fount of culture and industry today, but it was not so in ancient times. The greatest advances in ancient American civilization were made by the peoples of the American Southwest, the Valley of Mexico, the Maya lands, and Peru. The great Aztec, Maya, and Inca emperors would no doubt have looked upon the New England peoples of the first thousand years C.E. as backward.

When the first European explorers arrived in what would become New England, they found Algonquian tribes such as the Wampanoags who hunted turkeys, deer, moose, beaver, and smaller animals; angled for fish and collected clams and lobsters; and raised corn and beans, pumpkins, and tobacco.

A Wampanoag wetu (house) at Plimoth Patuxet Museums, Plymouth MA.

Attuned by tradition to their environment, the Algonquian peoples lived simply but well. They did not always get along with one another, however—intertribal warfare was common.

There was no center of power among the New England tribes as there was in the Iroquois confederacy of New York, which offered a focused and sustained resistance to the encroachments of European settlers.

The Explorers

Vikings & Vinland

Historians think that the Vikings were the first Europeans to explore North America's shores, but there is evidence, none of it conclusive, that the discoverers may have been Irish, Spaniards, or Portuguese.

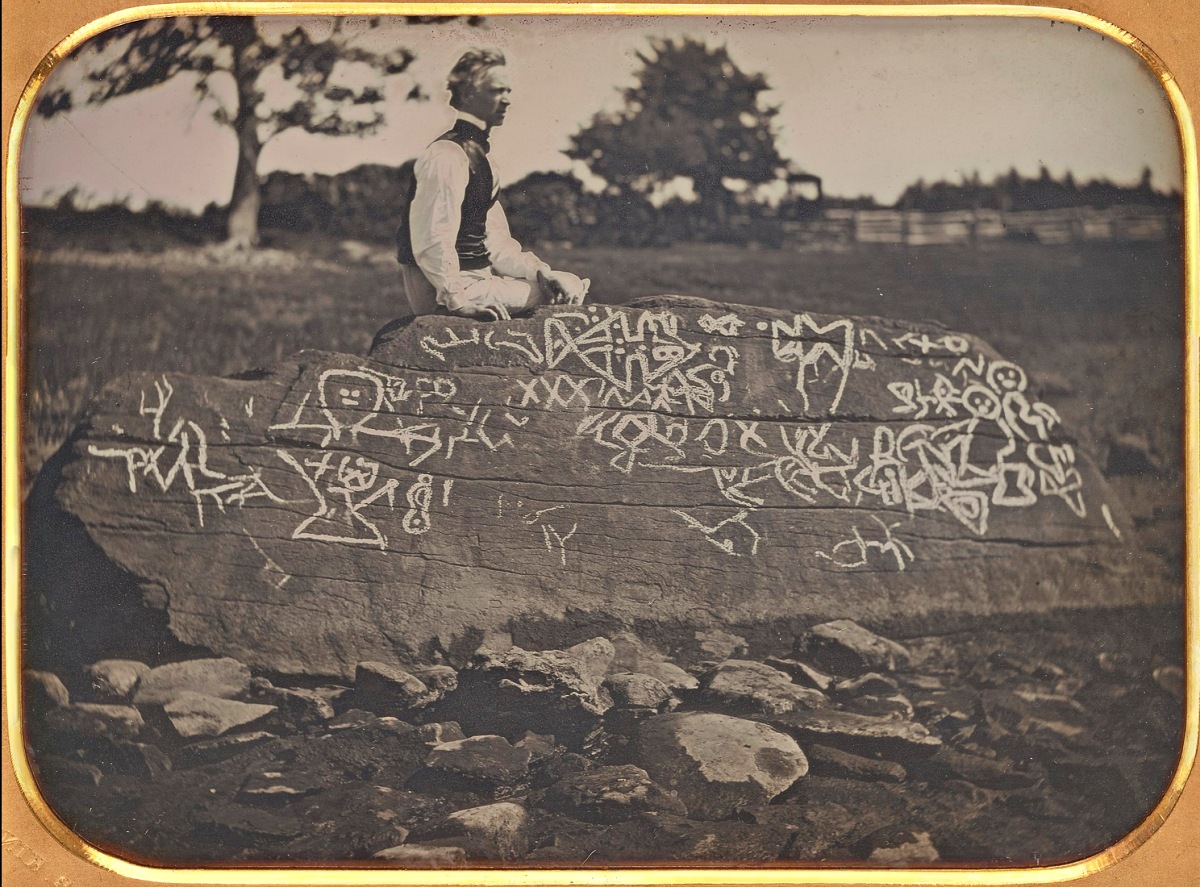

Dighton Rock

Early settlers of New England discovered a 40-ton boulder by the Taunton River marked with inscrutable incisions and "hieroglyphs." Ethnographers and epigraphists have puzzled over the rock and the cuts ever since. Claims have been made that the markings were made by Natives, or Norse, or Portuguese, or Chinese explorers, but no convincing case has ever been made.

Daguerrotype (c. 1853) of Dighton Rock and artist-soldier Seth Eastman, with the incisions marked in white.

Want to try your luck? Visit the Dighton Rock Museum in Dighton Rock State Park in Berkley MA.

But we know that the Norse came to this area about the year 1000 CE, and may have founded settlements in the land they called Vinland. Though the land was fruitful, the settlers found it hard going, mostly because the indigenous peoples fought the settlers ferociously.

The great Nordic leaders did not judge the land to be worth the deaths of many of their people, so they withdrew to their more easily ruled settlements in Greenland and Iceland.

Columbus, Cabot & More

By the time the intrepid Columbus set out on his epoch-making voyage 500 hundred years later (1492), Europe had become ready to profit from discoveries of new lands.

Columbus was followed by other explorers, including Giovanni Caboto (known as John Cabot), who sailed under the English flag in 1497 and claimed all of what would become New England for his master, King Henry VII.

Then there was Giovanni da Verrazzano, another Italian explorer sailing for François I, King of France. Verrazzano sailed the coast of North America between Cape Fear, North Carolina and Newfoundland, documenting New York Bay and Narragansett Bay in 1524.

The English Claim

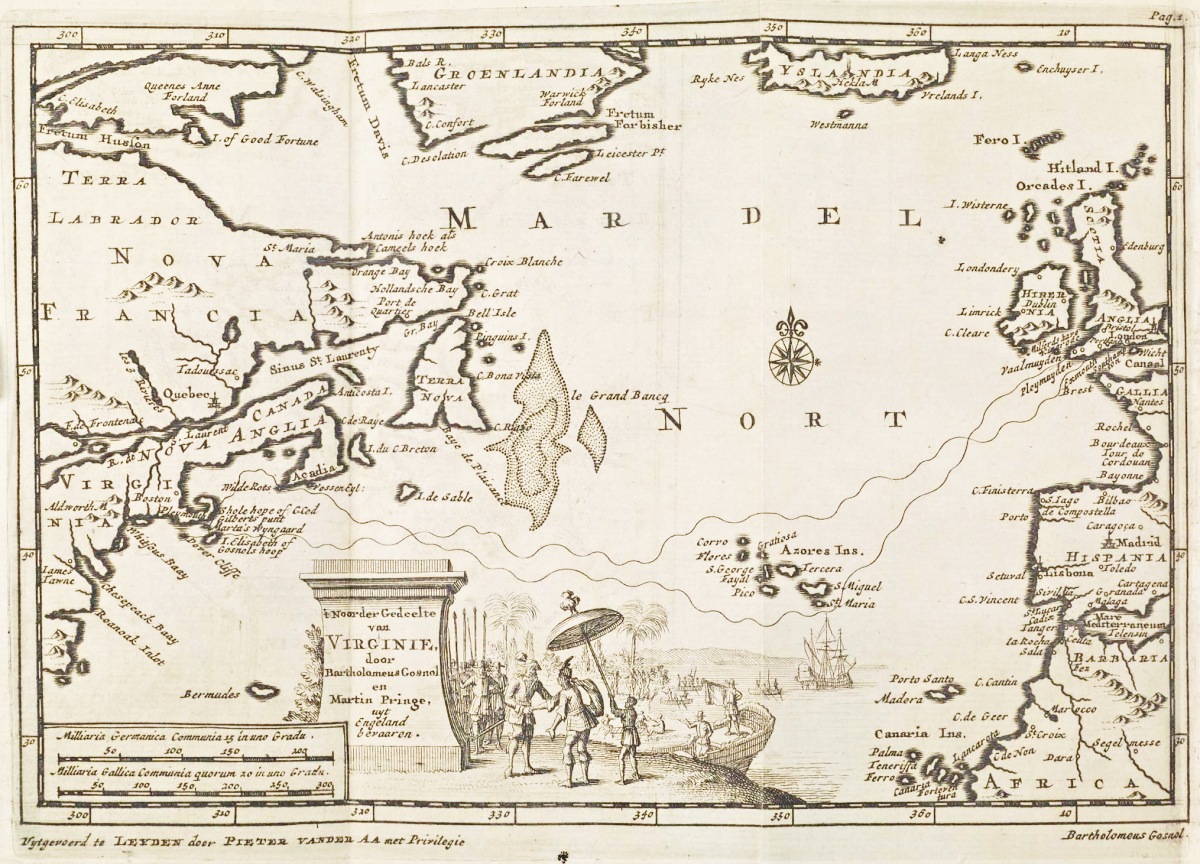

It took a century before the English monarch was ready to exploit his claims. During the early 1600s, expeditions were sent out under Sir Humphrey Gilbert, Bartholomew Gosnold, Martin Pringe, and George Weymouth.

Gosnold & Pringe's map of the New World.

These brought back useful intelligence on the new land (and Weymouth brought back a Native American named Tisquantum—called Squanto by the English—who learned English before returning to his homeland), but it was Sir John Smith who studied the land seriously with an eye to colonization, and who gave it the name New England.

The Pilgrims

Puritanism began in the Church of England during the 16th century as a movement to "purify" and simplify the church and bring its practices closer to those described in the Bible.

Before Gilbert, Gosnold, and Smith set out for the New World, several hundred Puritans had already left England for Holland in search of religious freedom. Unable to reform the Church of England and unwilling to adhere to it, members of a Puritan congregation in Scrooby, near York, emigrated to the Netherlands in 1607.

Their stay in Leyden was not a happy one, since they found the morals of the local people to be less than strict; so a number of these Puritan pilgrims set sail from Leyden, stopped in Southampton, and finally 102 of them set sail for the New World in 1620 from Plymouth, England, in a small ship called the Mayflower, along with some other English immigrants not so fervent in their beliefs.

After a difficult voyage of nearly two months, these Pilgrims first landed on Cape Cod but found its soil poor and water scarce. Before sailing to look for better land, they composed the Mayflower Compact to govern their nascent colony.

The Puritan, a statue by Augustus St Gaudens, in Salem MA.

They landed in Plymouth, on Massachusetts Bay, in December of 1620. During the ensuing difficult winter, with food scarce, scurvy rampant and shelter primitive, about half of the Pilgrims died of disease and privation. But luck was with the rest: Squanto, George Weymouth's prisoner, found them and persuaded Massasoit, sachem (chief) of the Wampanoags, to agree to 50 years of peace between his people and the colonists.

In 1621 more colonists arrived, and in a few years Plymouth was a sturdy colony. At first, land was held and worked in common, but this system was abandoned when it was realized that family plots would be worked more diligently. By 1640 there were 35 Puritan churches in New England.

(You can relive the early days of Pilgrim America at Plimoth Patuxet Museums in Plymouth MA, an authentic recreation of a Wampanoag village and the first Pilgrim village in the New World as they might have been in 1627).

Colonial New England

The Founders, as they are called, were followed in 1628 by another group of Pilgrims who established the colony of Massachusetts Bay. By 1637 the colony had several thousand inhabitants, and new towns were being founded up and down the coast, and even inland at Concord, Dedham, and Watertown.

The Puritan settlers must have seen a bright future, for in 1636 they set up Harvard College to educate young men for the ministry.

By 1640 there were sturdy communities of settlers in Connecticut and Rhode Island as well as in Massachusetts.

Henry Whitfield House (1639), Guilford CT, the oldest house in Connecticut.

By 1680 the indigenous peoples who had lived here before the coming of the settlers were reduced to only a few thousand souls through fierce warfare, European-introduced disease, and alcohol addiction.

By 1692, the population of the New England colonies had grown so large, with so many non-religious immigrants, that Puritan influence waned, and what had been founded as a theocratic society based on religious law became a secular polity based on secular law.

Revolutionary New England

New England's colonists had built their own prosperity despite laws promulgated in London that placed burdens and restraints on their economic activities. Governors sent out by the king were universally disliked, and often forced to return home by the cantankerous colonists.

It was King George III (reigned 1760-1820) who forced the issue, refusing to bear the irritation of the Americans' independent spirit any longer. Taxes were imposed on the colonies, even though the colonists had no elected representatives and no voice in Parliament. Resentment grew as the colonists chafed under the burden of taxation without representation.

The king was determined to force the issue, but it was the colonists who lit the fuse on the powderkeg. In March 1770, a crowd of Bostonians began taunting royal army sentries, and soon the mob got out of hand. Greatly outnumbered, the soldiers fired into the crowd, killing five citizens in what would be known as the Boston Massacre.

Life in Boston was outwardly peaceful for a few years, but king and Parliament were still determined to rule the unruly colonists, and the colonists were determined not to permit interference with their privileges of self-government, now a century and a half old.

The Boston Tea Party

As a symbol of London's supremacy, a tax was placed on tea shipped to the colonies. Tea was to New England then what coffee is to America today, and the tax was widely reviled, not so much for its economic impact, which was minimal, but because of its symbolic importance: virtually everyone drank tea, and thus everyone was forced to pay the tax.

The political temperature rose as American patriots formed secret societies, such as the Sons of Liberty and the Committees of correspondence, and worked out plans of resistance to London's control.

In the autumn of 1773, matters came to a head as the patriotic activists insisted that the king's governor order HMS Dartmouth, arriving in Boston with a cargo of taxable tea, to go back where it came from. Governor Hutchinson would not give the order, so on the night of December 16, bands of patriots disguised as Indians and blacks boarded the Dartmouth and two other ships and dumped their cargoes of tea into Boston harbor. The night's action became known as the Boston Tea Party.

When London learned of this rebellious act, laws were passed that were meant to strangle the colonial economy and to teach the nasty colonists a lesson. The political temperature in New England neared the boiling point.

Battle of Lexington

Seeing war as inevitable, farmers and tradesmen began to stockpile arms, ammunition, and matériel. Royal spies reported a large cache of arms and supplies at Concord, twenty miles northwest of Boston.

Realizing that the colonists' arms collecting must be stopped, the British ordered an expeditionary force to march secretly from Boston to Concord on the night of April 18, 1775, and to make surprise searches of suspected illegal arms caches at dawn the next day.

American spies learned of the British plan and set up a system to warn their countrymen. If the redcoats under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Francis Smith, departed Boston along the isthmus that linked it to the mainland, one lantern would be hung in the steeple of Boston's Old North Church. If the troops instead boarded boats to row across the water and march on a different route, two lanterns would be hung.

As the British filled the boats, two lanterns appeared in the steeple, easily visible from the far shore where Paul Revere, William Dawes, and Dr Samuel Prescott waited on horseback. These messengers rode into the dark hinterland, sounding the alarm in each village. Revere was captured by a British patrol on the road beyon d Lexington, but Prescott got through to Concord. The American intelligence network was so good that the citizens of Lexington and Concord leapt from their beds long before the British advance force was anywhere near.

We don't know what went through the minds of the Minutemen and the colonial militia as they waited in the chilly dawn to hear the crunch of the redcoats' boots in the streets of Lexington and Concord. Whatever their thoughts, they had every right to be frightened, since they, small simply-trained bands of farmers and tradesmen, were about to face 700 of the world's best professional soldiers.

As dawn broke on April 19, 1775, about 77 Lexington Minutemen, outnubered ten to one, faced the British troops on Lexington's town green.

Seven hundred redcoats fire at 77 Minutemen.

The Minutemen were ordered by Major Pitcairn to disperse. They stood their ground. Taunts were exchanged. A shot was fired, and that triggered a battle.

When the smoke cleared, eight Minutemen were dead, and the British troops went on a rampage that was stopped only with difficulty by their commanders, who immediately marched them in the direction of Concord.

(The Lexington Fight is re-enacted each year on Patriots Day. More...)

Battle of Concord

Word of the Lexington engagement was rushed to Concord (map), where the Minutemen and militia, now numbering about 250, retreated across the North Bridge (map) over the Concord River in the face of the superior British force.

The British commander established his headquarters in the Wright Tavern (which still exists) and set his troops on the search for arms.

Wright Tavern and the First Parish meetinghouse (church) in Monument Square, Concord MA.

Seven companies (about 100 men) were sent to cross Concord's North Bridge and proceed to Barrett's Farm, where British intelligence had determined that military equipment was hidden.

Rebeckah Barrett, wife of Concord militia Colonel James Barrett, is interrogated by British officers about illegal military arms and matériel.

A small force of about 95 soldiers under an inexperienced commander, Captain Walter Laurie, was left behind to secure the bridge.

The Minutemen took up positions atop Punkatasset Hill, only 300 yards (274 meters) northwest of the bridge, as reinforcements of Minutemen and militia from surrounding towns—Acton, Bedford, Lincoln and Sudbury —continued to arrive, augmenting their force to about 400 men.

As the redcoats in the center of Concord pursued their mission, they discovered and burned some wooden gun carriages (cannon mounts). The fire spread to the meetinghouse (church), and the smoke rising from the town, easily visible from Punkatasset Hill, convinced the Minutemen that the British were burning their homes.

"Will you let them burn the town down?" Adjutant Joseph Hosmer cried as a call to action.

The Minutemen advanced down the hill under orders to fire only if fired upon. The British force holding the bridge retreated across the bridge. A redcoat officer began to remove planks from the bridge in order to slow the Americans' advance, which only increased the Minutemen's anger.

When the two forces were only about 50 yards (46 meters) apart, a shot rang out—most probably from an exhausted, inexperienced, frightened British soldier. Hearing it, other British soldiers began to fire as well, and the Minutemen responded.

The battle lasted only a few minutes, but when the musket smoke cleared, half of the British officers were wounded and a dozen of their troops were dead or wounded. They fled toward the town seeking reinforcements.

Victorious Minutemen cross the North Bridge in Concord MA.

The shot heard 'round the world was fired from the Minutemen's muskets at Concord North Bridge, where this band of farmers held off professional soldiers. But this first victorious battle of the American revolution was actually won by the American militias as the British retreated toward Boston. Sniping from behind trees and stone walls along the road all the way back to Boston, Minutemen brought the British casualty count up to 200, a grievous and embarrassing loss for the powerful, well-equipped forces of the Crown.

News of the events in Lexington and Concord spread like wildfire through the British colonies in America, forcing every American to choose sides: would one be loyal to the Crown, or committed to the revolutionary cause? There was no middle ground. (The Battle of Concord is re-enacted annually on Patriots Day. More...)

Battle of Bunker Hill

In June 1775, two months after the battles of Lexington and Concord, the Continental (American) army besieging Boston learned that the British were about to send troops out to occupy the hills surrounding the town, including Bunker's Hill in Charlestown.

On June 17, 1775, Colonel William Prescott of the Continental army ordered his force of 1200 men secretly to march from Cambridge via the isthmus of Charlestown Neck, to occupy Bunker's Hill during the night and construct a small earthwork fortification.

When the British awoke, they found the Americans in command not only of Charlestown Neck, but indeed in a position to shoot into the town of Boston itself.

A force of 2200 British regulars was dispatched by longboat from Boston across the Charles River to Charlestown to take the hill. Landing near where the USS Constitution ("Old Ironsides") is now moored, the regulars then sat down and ate lunch, giving the American forces more time to build defenses.

"Old Ironsides" and the Bunker Hill Monument, Charlestown, Boston MA

In mid-afternoon the regulars attacked, only to be driven back by American fire. Another British attack was ordered, and again it was thrown back. The ammunition of the defenders running low, Colonel Prescott cried to his men, "Don't fire until you see the whites of their eyes!"

It was not long before the Americans' ammunition was exhausted. The third British assault brought the attackers to the top of the hill and into hand-to-hand combat with the defenders.

The British muskets had bayonets. Most of the colonial muskets did not. The Americans, outnumbered and outgunned, were able to retreat in good order across Charlestown Neck to fortified positions in Cambridge, carrying most of their wounded with them.

Though the British then took possession of the hill and all Charlestown, the Battle of Bunker Hill was for them a Pyrrhic victory: 226 regulars were killed and 800 wounded—nearly half their force—including 100 commissioned officers, a grievous blow to the British military command in North America.

American losses were lighter: 140 killed, about 310 wounded—about 1/3 of their force.

The Battle of Bunker Hill heartened the American forces and their cause, and was still in living memory when, in 1827, a campaign was begun to raise money for a fitting monument to the battle.

The Bunker Hill Monument.

Declaration of Independence

A few weeks later on July 4, in Philadelphia, American leaders signed a Declaration of Independence from Great Britain.

Though many of the most important battles of the Revolutionary War were later to be fought in New York and Pennsylvania, New England prides itself on having been the place where it all began.

Patriots Day (April 19) is a holiday in Massachusetts, and hundreds of citizens and visitors turn out at dawn to witness reenactments of the battles of Lexington and Concord staged by groups in period uniforms.

Early America

By 1781, the Revolutionary War was over and the American colonies were free and independent states.

But the forging of a strong and effective central government for the former British territories would not be accomplished until 1789.

In the meantime, the removal of British legal restrictions on trade meant that New England merchants were at last free to trade with the world as they liked. New Englanders put to sea in ships built in Maine, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut, and were soon returning with the riches of Europe, Africa, China, and India in trade.

The Friendship, a square-rigged clipper ship that brought the wealth of the world to Salem MA.

Whaling ships out of Salem and New Bedford brought back whale-oil wealth of similar greatness.

Though the renewal of war with Great Britain (the War of 1812) disrupted New England's progress for a time, the seas were soon open again.

The Industrial Revolution

Early New England settlers were farmers by necessity. New England's geography makes it difficult for farming, but its many rivers and creeks with their potential for water-power make it fine for industry. Water-powered grist mills, sawmills and other small industries thrived. (You can still see grist mills in operation at the Wayside Inn, in Sandwich and Chatham on Cape Cod, and in other places.)

Then, in 1789, across the open sea from England, came a young man named Samuel Slater (1768-1835) who had worked in the new and revolutionary English cotton-spinning factories.

Though it was against British law to export technical information of the spinning machines, which were making Great Britain the world's wealthiest textile producer, Slater slipped out of the country with knowledge of English spinning machine design and took ship for New England.

Arriving in Rhode Island he, along with Moses Brown and William Almy, established a cotton-spinning mill at Pawtucket, based on his knowledge of English machine design. The mill revolutionized the weaving of textiles in the New World, and set the stage for New England's great weaving industry.

Slater's knowledge of continuous production and the principles of industrial management allowed him to create the successful "Rhode Island System" of industrial production. Soon he went on to manufacture machinery to sell to other cotton mills.

Old Slater Mill National Historic Landmark, Pawtucket RI.

Eli Whitney's cotton gin (1794) greatly improved the efficiency of cotton preparation and thread quality, speeding expansion.

Throughout the 19th century, as New England's clipper ships and whalers swept through the world's oceans, land-bound New Englanders exploited the region's waterpower resources to run their new mills, and industrial towns sprang to life along New England's rivers.

The textile factories grew and grew, and some, like the gigantic Amoskeag Mills in Manchester NH, had many-windowed facades that marched along the riverbank for more than a quarter mile.

Amoskeag Mills, Manchester NH, once produced the most cotton cloth in the world.

An important aspect of the new New England industrialism was Slater's concept of inviting entire families to move to factory towns. Next to the factories houses were built for the new workers. Company stores and company-financed civic buildings filled the streets of the new towns, which were founded on the wealth from weaving.

From some of the factories it was not textiles but machinery, firearms, shoes, watches, and instruments that marched out the doors on their way to the markets of the world.

New England inventors and engineers gained a reputation for ingenuity that survives today, and samples of "Yankee ingenuity" are still proudly displayed.

New England's commercial success brought New Englanders wealth and sophistication. Boston, chief city of the region, was proud to call itself the "Athens of America." But times change, and changing times brought changed circumstances to the region in the next century.

New England Now

Millions of immigrants who had come from abroad to share in New England's commercial boom were left with minimal skills in a diminishing job market. New England's farms, set on rocky soil in a northern climate, were outproduced and out-sold by the vast farms in other areas of the country.

The stock market crash of 1929 and its aftermath spelled the bitter end of New England's golden age. What had once been America's richest, proudest, and most cultured region was now economically depressed, politically corrupt, and spiritually defeated.

But New England was still beautiful, historic, and proud. In the years after World War II, New Englanders realized that their land had other kinds of wealth. New England's hundreds of colleges and universities were leaders in education. The New England landscape was sprinkled with graceful towns and villages. New Englanders were as ingenious as ever, and the chilly waters of the Atlantic still held a wealth of seafood, so New England survived, and even prospered again.

In recent decades, graduates of New England's universities, no matter where they came from, settled here and founded small computer and life sciences companies that became large companies employing tens of thousands.

The sturdy old 19th-century textile mills of brick and granite were recycled as company offices and factories. The name of Route 128, (now I-95) Boston's ring road, became synonymous with the computer industry, and several Boston-area neighborhoods—Kendall Square, Seaport, Longwood—are synonymous with high-tech and biotech. Finance and insurance add to the region's wealth.

New England's picturesque towns and villages found a new vocation as the great old houses were transformed to historic inns, and the more modest houses began to provide bed and breakfast to travelers and vacationers.

Connecticut, Massachusetts and New Hampshire are among the wealthiest states in the country.

New England Facts & Firsts

•Basketball was invented in 1891 by Dr James Naismith in Springfield MA. You can visit the Basketball Hall of Fame there. Four years later, William Morgan invented volleyball in nearby Holyoke MA.

Basketball Hall of Fame, Springfield MA.

• Dollar bills are printed on paper produced by the Crane Paper Company of Dalton MA, main paper supplier to the US Mint.

• Great Barrington MA was the first town in the world to have electric street lights, in 1886.

• Sylvester Graham (1794-1851) of Northampton MA advocated a diet of vegetables and coarse-milled grains, so he invented the Graham cracker.

• Boston is at a latitude similar to Barcelona, Rome and Istanbul.

• Harvard University, America's oldest institution of higher learning, was founded in 1636. It has the largest academic research library in the world.

Massachusetts Hall (1720), Harvard University, Cambridge MA

• Of the 200+ of people accused of witchcraft in Salem MA in 1692, only one confessed—and she claimed others had forced her into evil. At least 25 people were executed or died in jail because of the superstition.

• Mount Washington (6288 feet/1917 meters), with the highest summit east of the Rockies, had the highest winds ever recorded that was not part of a tropical cyclone: 231 miles per hour. The summit qualifies as an arctic climate zone.

Mount Washington & the Mount Washington Hotel, Bretton Woods NH.

• Boston's subway system (underground railway, Metro) was the first to be built in the western hemisphere.

• The Smiley (or Smiley Face) was created in Worcester MA in 1963 by artist Harvey Ball (1921-2001).